Death Disco: Pet Shop Boys and AIDS

I’m a queer man in my late 40s [as I self-identified at the time; I’m now a non-binary person in my mid-50s], and my community — especially the generation immediately prior to mine — was demolished by AIDS. These days it may be seen as benign as diabetes — i.e., take your daily meds and you’re basically fine — but in the ‘80s, and into the early ‘90s, it was basically a death sentence. When I was 16, in 1987, openly gay San Francisco journalist Randy Shilts published And the Band Played On, the first major non-fiction book on the epidemic. I wasn’t sexually active at the time, and didn’t know anyone who was HIV-positive in my small, northeastern Indiana hometown, but I knew enough from the media to know that AIDS was serious business. As a precocious, albeit closeted teenager, I immediately ordered the book from QPB, the Quality Paperback Book Club, an offshoot of the famed Book of the Month Club; I ended up doing a term paper for my Honors English class on AIDS after reading Shilts’ tome.

To the best of my recollection, I didn’t include any mentions in said paper of cultural responses to the epidemic, because as far as I knew, there weren’t any. However, unbeknownst to me, there had already been a handful of pop songs released which took AIDS as their subjects. Cyndi Lauper’s sophomore album, 1986’s True Colors, featured “Boy Blue” (which would be released as the album’s fourth single in 1987 and became her first flop, peaking at #71 in the U.S.), a song which Lauper co-wrote about a friend who died of AIDS. Prior to that, what appears to have been the first such song came from the experimental British duo Coil, in the form of their funereal 1985 cover of the Northern Soul classic “Tainted Love,” whose title they chose to interpret rather literally. Their version of “Tainted Love” was released as the B-side of their debut single, “Panic,” with all of its proceeds going to the Terrence Higgins Trust, the UK’s first charity devoted to HIV and AIDS (started in 1982). Its video laid things even more bare: directed by the duo’s Peter Christopherson, it featured his musical and personal partner Balance as a hospitalized AIDS patient -- along with a cameo from Marc Almond, not only the voice of Soft Cell, who took “Tainted Love” to #1 in 17 countries in 1981-82, but a fellow queer man very aware of AIDS at the time; he told The Guardian’s Marc Fisher that he first heard about the disease in a taxi in New York City in 1981, year zero for the epidemic. Some have suggested that his character in the video is the angel of death.

In 1987, a couple more songs about AIDS were released. The openly gay British duo the Communards, led by Jimmy Sommerville, formerly of the openly gay trio Bronski Beat, released their second album, Red, which featured “For A Friend,” a simultaneously heartbroken and furious song about Sommerville’s late friend and Irish gay activist Mark Ashton. And then-non-openly gay British duo Pet Shop Boys dropped their sophomore effort as well. Actually followed up the monster worldwide success of their debut, Please, and featured not one, not two, but three songs with lyrics implicitly about AIDS. You had to know to look, and for what you were looking, however; the Boys were keeping their cards close to their vests.

That said, from here on, the duo of Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe -- Tennant eventually came out publicly in 1994, in an interview with British gay magazine Attitude; Lowe has yet to explicitly do so, but it is commonly assumed that he’s also queer -- wrote, recorded, and released as many as a dozen songs about HIV/AIDS and its impacts. (I say “as many as” because some of these songs are open to interpretation.) This is important for the historical record, as we look back on how the music industry responded (or didn’t) to AIDS, but was also significant in its moment, as PSB were speaking directly (though often in code) to those being most affected by the health crisis -- and they were doing so directly through their Imperial Phase, which assured that plenty of people heard what they were saying, seemingly with no fear of how doing so might “tar” them. Here I’ll discuss how Pet Shop Boys have done more than anyone in popular music to artistically chronicle AIDS, especially over its first 15 years.

(Tennant and Lowe, by the way, were themselves a huge help in writing this paper. For the deluxe remastered editions of their catalog, all of which have been re-issued over the past two years, they gave extensive interviews to journalist Chris Heath, with whom they’ve had a working relationship since their 1990 book Pet Shop Boys, Literally — so they’ve openly discussed every single song in their catalog. In addition, late last year, Neil Tennant published One Hundred Lyrics and a Poem, featuring the 100 songs he’s written which he feels looked best on the printed page, along with some commentary/background on each selection. To say that I’m grateful — not just for the sake of this paper, but as a massive fan — is quite an understatement.)

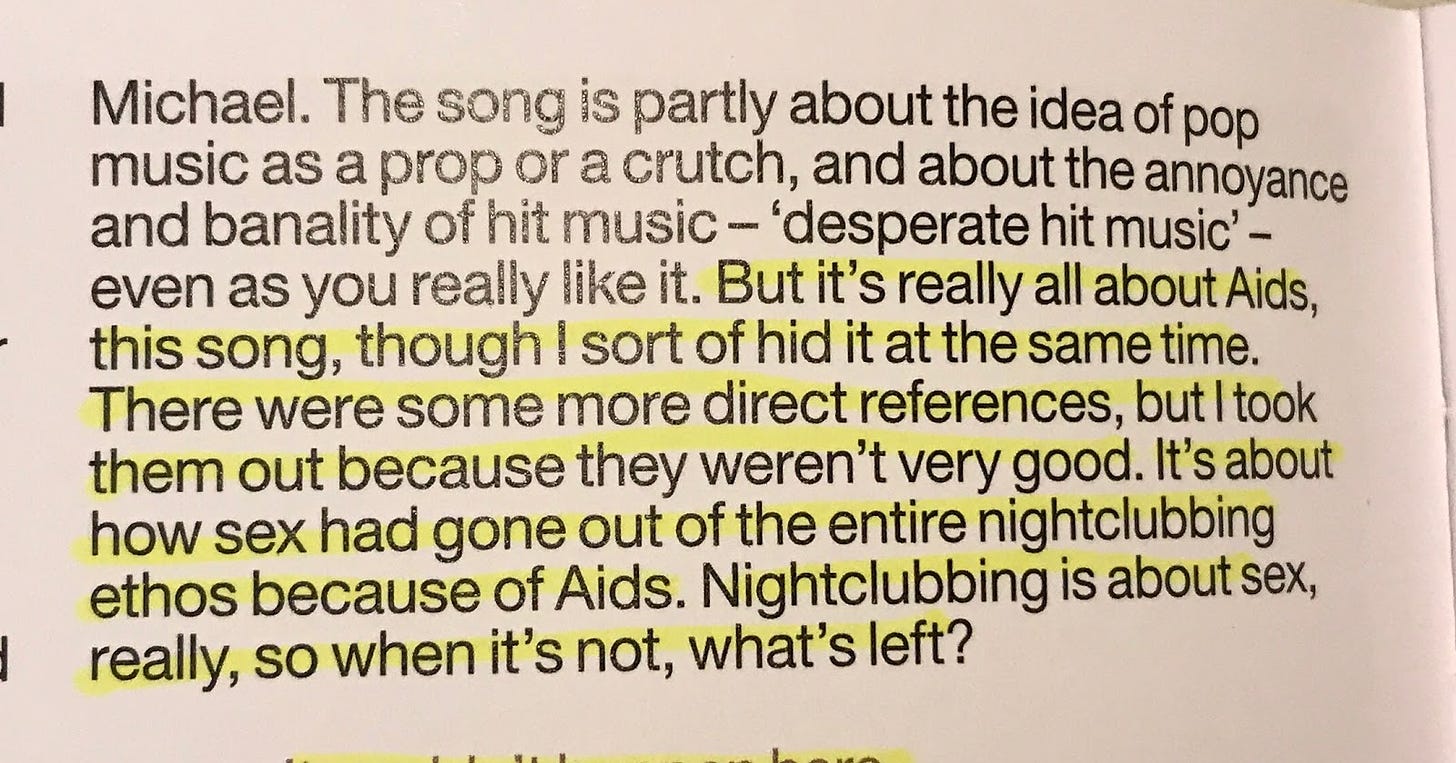

Some of the songs Tennant and Lowe have penned about AIDS are absolutely oblique. One of those, one of the Actually trio, is “Hit Music.” About it, Tennant says,

Almost a decade later, “Saturday Night Forever,” from 1996’s Bilingual, addresses similar ground, declaring, “I go where I go and I get there fast/Don’t stop me, I know that it’s not gonna last.” Dancing as fast as we can before the world ends.

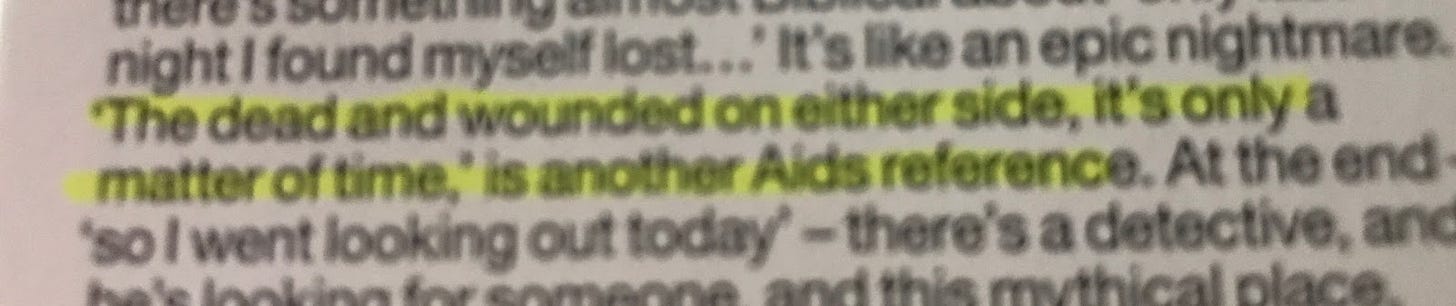

Back to Actually, “King’s Cross” is a little more direct than “Hit Music”:

And then there’s Actually’s coup de grace, “It Couldn’t Happen Here.” In the song, Tennant sings,

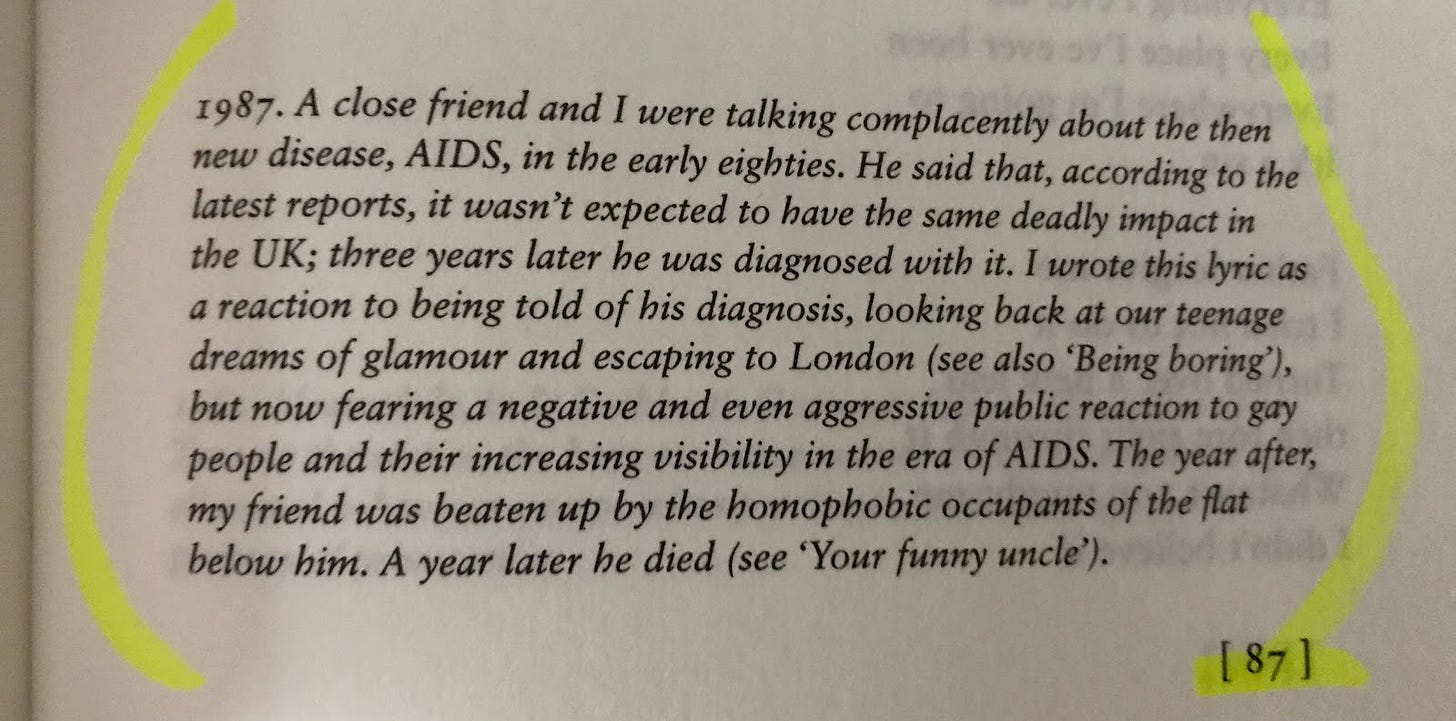

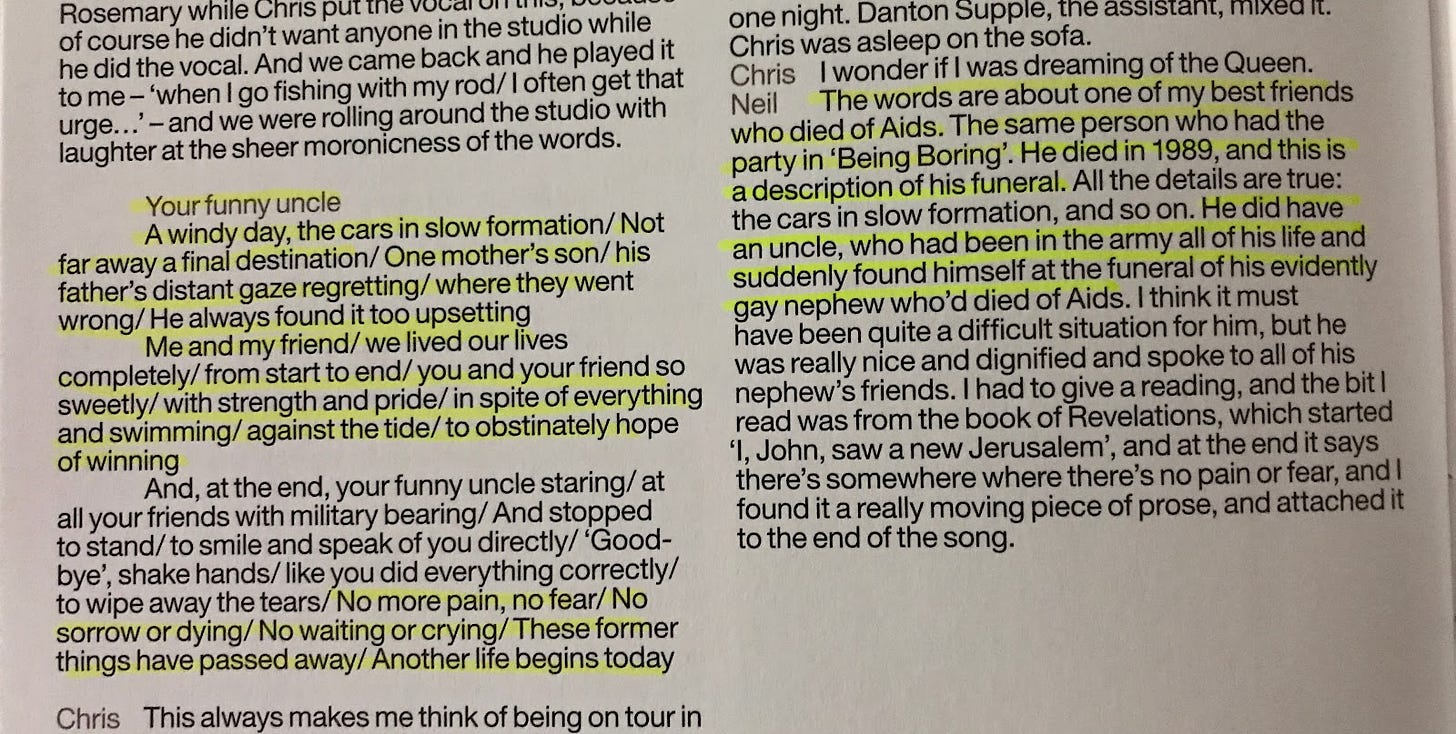

“It Couldn’t Happen Here” actually makes a triad of sorts with “Your Funny Uncle” (which was a b-side of their 1988 cover of the house classic “It’s Alright”) and Behaviour’s “Being Boring,” as all three songs reference the same late friend of Tennant’s. “Uncle” is about the friend’s funeral.

The words sung at the end of the song are adapted from Revelation 21:4, which Tennant read at the funeral:

And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.

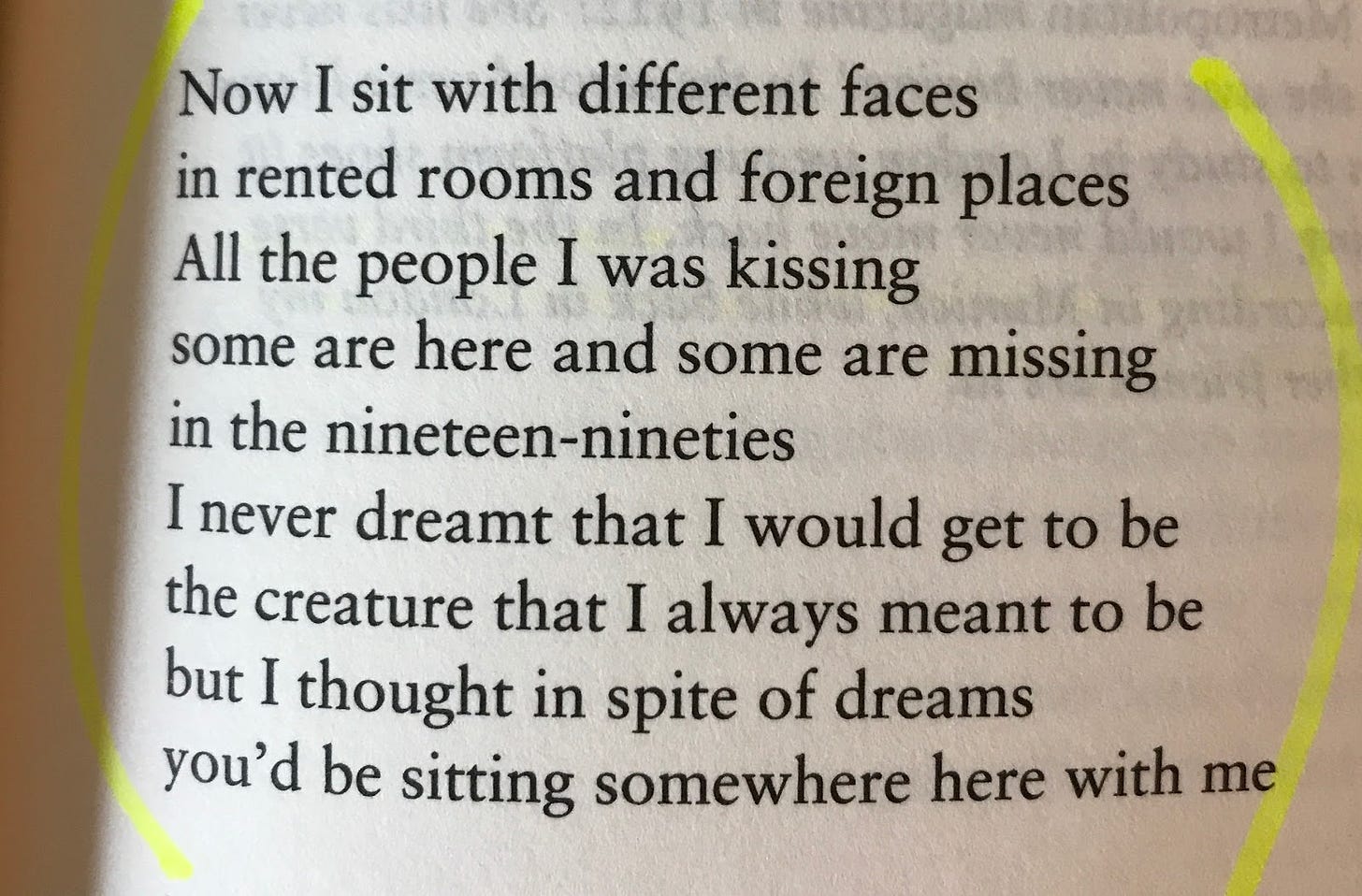

“Being Boring” is an elegiac look back at the same friend’s life.

Neil has, somehow, escaped the bullet of AIDS, while others of his friends are sick and/or dead. The B-52’s concurrent “Deadbeat Club” similarly looks back at “better days” of parties, et cetera, prior to the death of loved ones to AIDS — in their case, multiple friends, but most specifically their late guitarist Ricky Wilson. (My dear friend Alfred Soto spoke beautifully about the song at the same PopCon.)

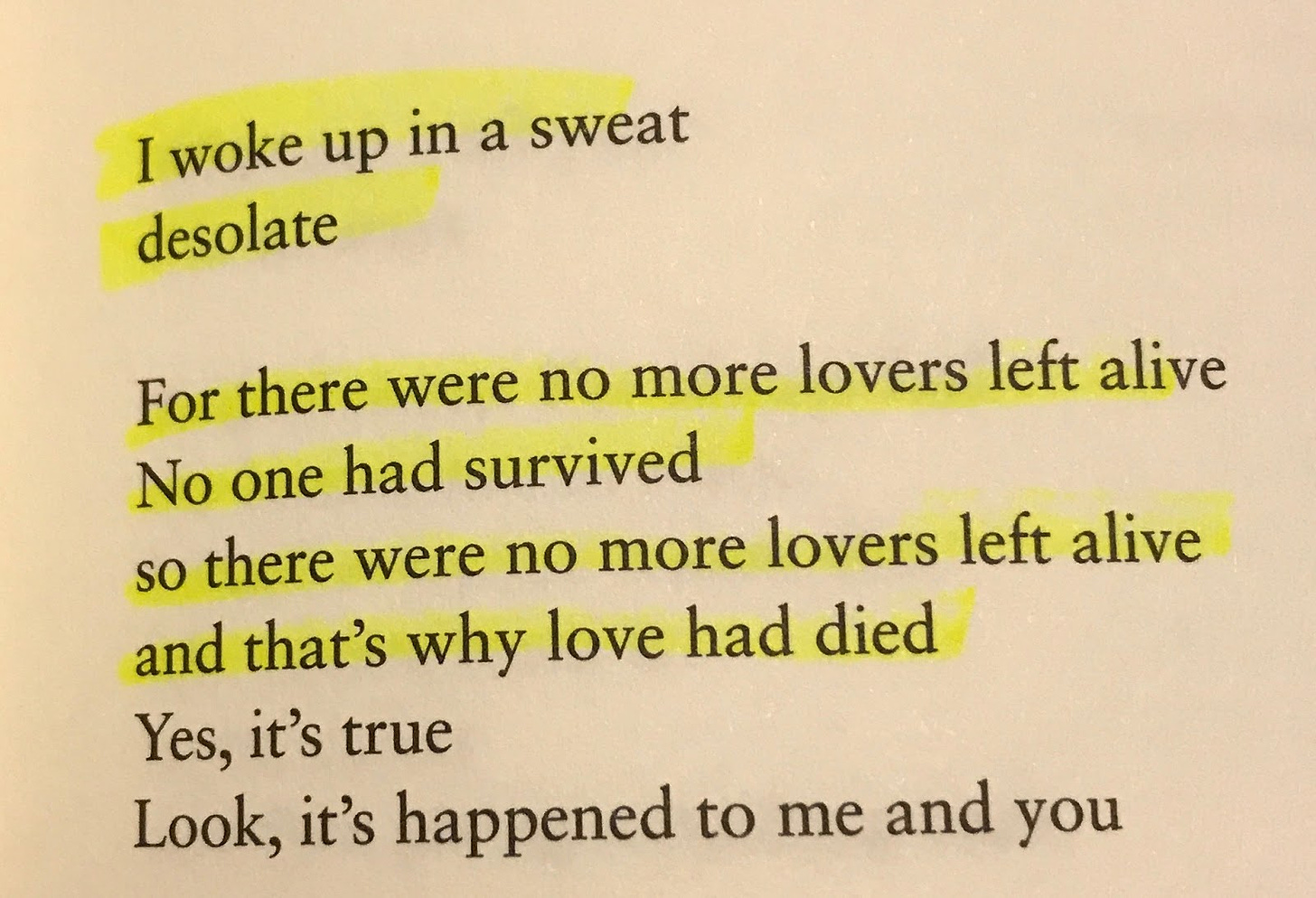

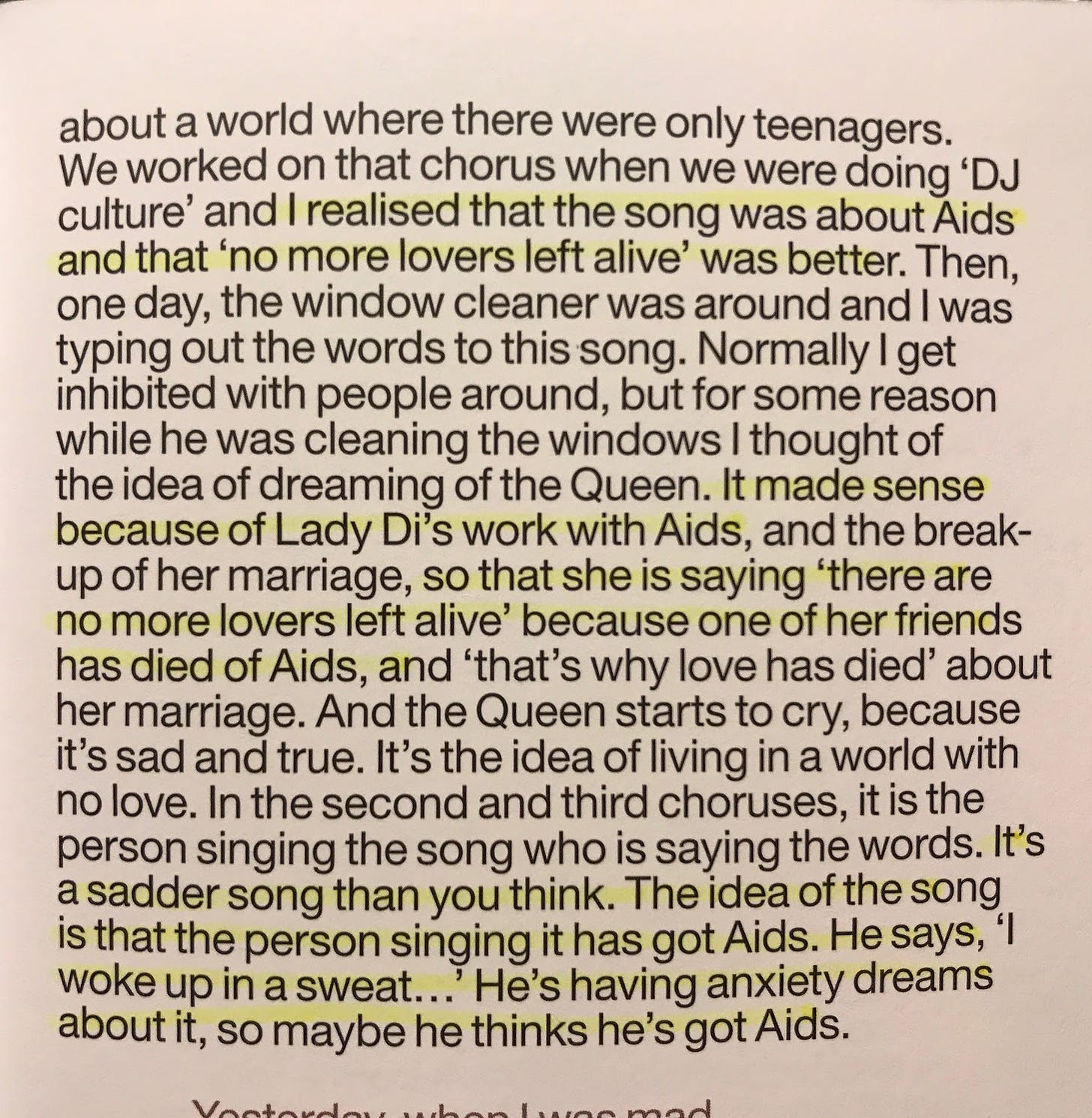

“Being Boring” is considered by many to be Pet Shop Boys’ quote-unquote ultimate song about HIV/AIDS and its effects; I might argue instead for “Dreaming of the Queen,” from 1993’s Very.

In doing my research for this paper, I realized that for nearly 30 years I’d been mis-hearing a key lyric: the final line going into the song’s first chorus isn’t, as I falsely thought, “and I replied,” but instead the more meaning-filled “and [Princess] Di replied.” The fact that it’s Diana, and not the song’s narrator, responding to Queen Elizabeth, makes the chorus that much more poignant. It’s Diana pointing out that there are “no more lovers left alive.” As she was a tireless advocate for the HIV/AIDS community, and as she was simultaneously, y’know, Princess Diana, that means something. That, in the song, matters. Greatly.

The reference to night sweats, especially, is about as literal as Tennant lyrics about AIDS have ever gotten.

Now, by this point, more artists -- and big ones at that -- were releasing songs about AIDS. Elton John released “The Last Song” as a single in 1992 -- his first single from which all proceeds went to his own Elton John AIDS Foundation. The song itself, which hit #21 UK/#23 US (and #2 on the US Adult Contemporary chart), is about a father coming to terms with his gay son, who is dying of AIDS.

Meanwhile, Madonna’s late 1992 album Erotica included the song “In This Life,” which took as its subject the deaths from AIDS of two major figures in Madonna’s life, Martin Burgoyne, an artist who was Madonna’s roommate and best friend in New York in the early ‘80s, and Christopher Flynn, her first ballet teacher in Michigan, and the first gay man she knew. So it’s not as if the greater pop world was completely ignoring AIDS at this point in time. But yet, the Pet Shop Boys still had more to say about the epidemic.

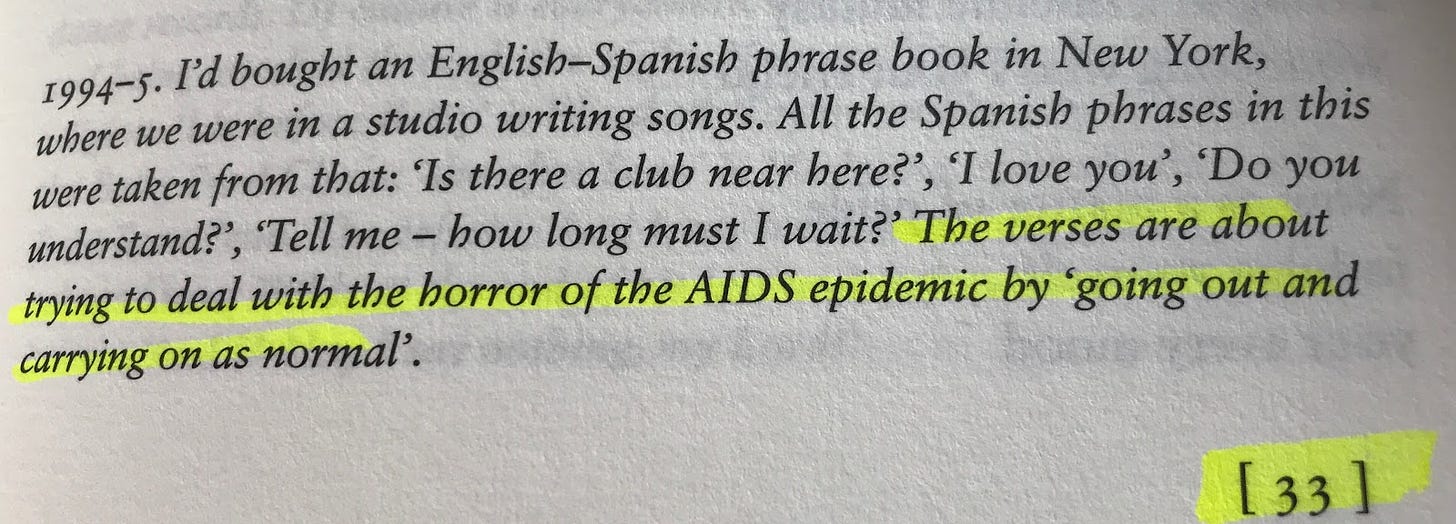

1996’s album Bilingual features “Discoteca,” another in Tennant’s line of “whatever else can you do but dance and go on as normal?” songs regarding AIDS:

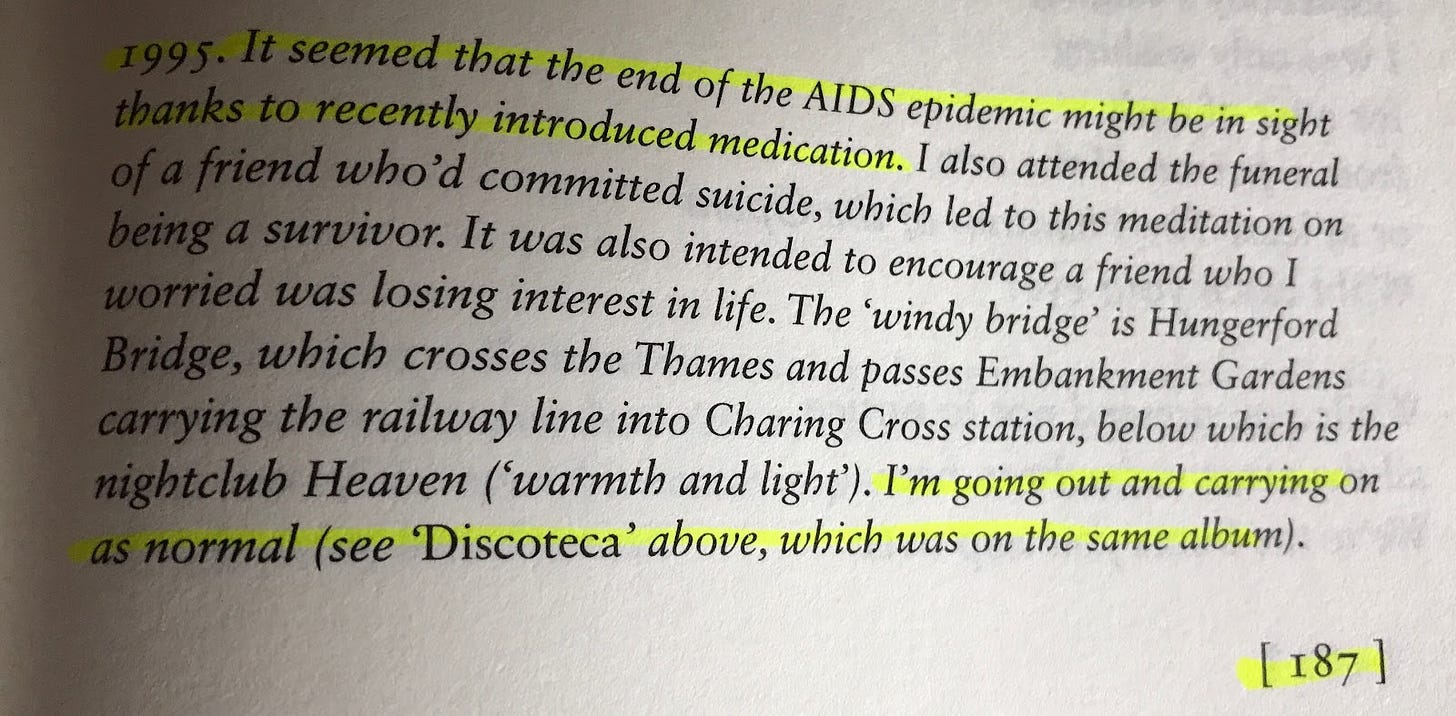

And the same album features “The Survivors,” which to my eyes and ears only really has one reading possible:

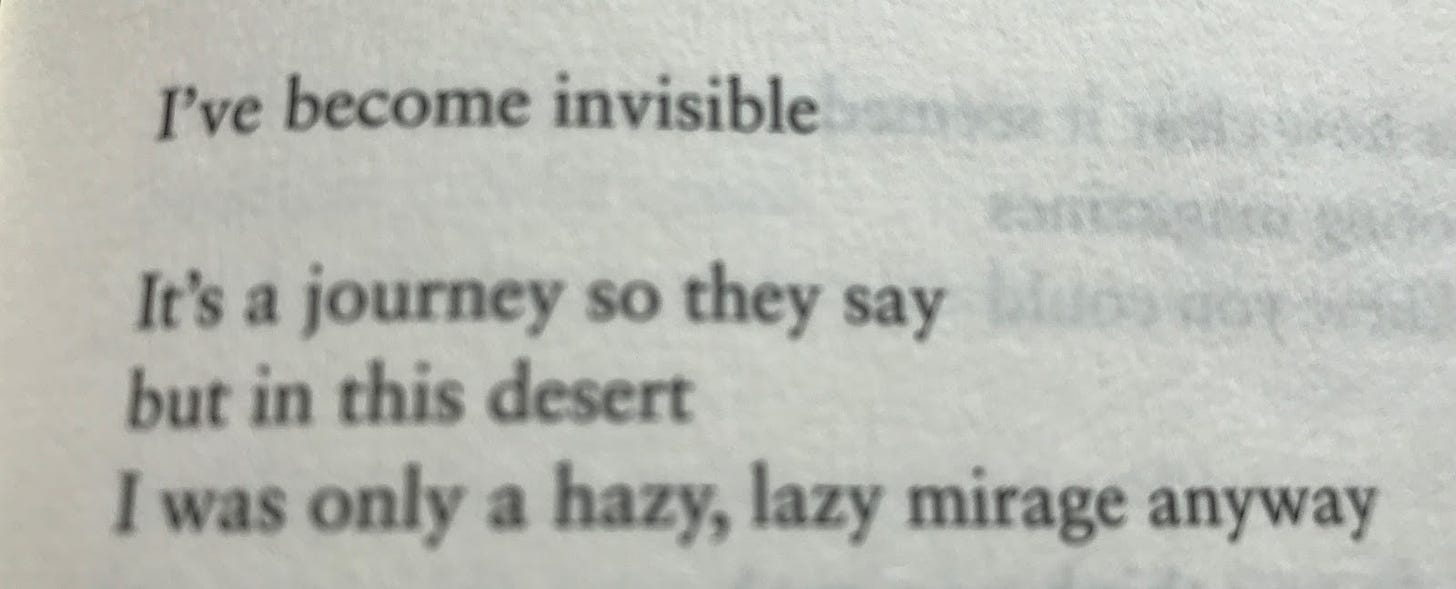

With the advent of protease inhibitors and PrEP and the like, AIDS has, as I mentioned at the start, become more of a quote-unquote manageable disease. Accordingly, Tennant (and Lowe) have perhaps felt less need to write songs about it. But occasionally, one will pop up in their catalog. In 2012, 31 years after the first reported cases of what the Centers for Disease Control considered AIDS, Pet Shop Boys released Elysium, their 11th studio album. Among its tracks is the incredibly poignant “Invisible,” about which Neil says:

And yes, the song can take on multiple meanings; lately, I’ve felt a strong connection to it through my depression. But it also most definitely has an AIDS lean, as well, if you consider it sung from the perspective of one who’s passed away.

And there are other artists who’ve done songs about the scourge of AIDS and its effects, too, that I’ve not yet mentioned, from Lou Reed’s “Halloween Parade” to multiple works by Diamanda Galas, to all of the songs discussed during the glorious roundtable discussion on songs about AIDS at 2018’s PopCon. But no one -- and I’ll say it louder for those in the back, NO ONE -- has done more to artistically chronicle their personal relationships with the disease and those affected by it than those titans of synthpop, Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe, aka Pet Shop Boys. I am grateful to them for their work.

[Photos of some lyrics and notes on lyrics taken from Neil Tennant’s book One Hundred Lyrics and a Poem (Faber & Faber, 2018). Others, along with selections from interviews, taken from the CD booklets for the deluxe editions of Pet Shop Boys’ catalog.]

[Presented at the Pop Conference, EMP, Seattle, in 2019.]

[Below is an expanded playlist to accompany this paper.]